The concealed horror of the war in Ukraine: Russian “filtration camps”

Many of us have read about the atrocities Russian troops inflicted on residents of Bucha, Ukraine, and other occupied areas. Shot civilians, including children, lying in the streets, some with their hands tied. Mass graves. Systematic rape. Many of the photos were too graphic to be published by most outlets. Such horrors are likely continuing in currently occupied territories.

But another, more concealed, horror awaits those who try to leave the occupied areas: Russian “filtration camps”. Russia is systematically screening civilians trying to escape, sometimes beating and torturing them during the process. Those who don’t pass the “filtration” are taken away and killed. Because the Russians control the territory on which filtration happens, they are able to hide the evidence and the bodies. At this point, most of the evidence on what happens in these camps is coming from those who have passed filtration or escaped. But the evidence that is emerging reinforces the importance of helping Ukraine win this war as quickly as possible and committing to holding those responsible fully accountable for the atrocities.

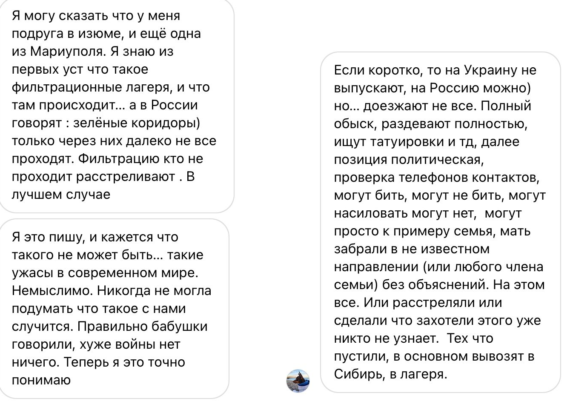

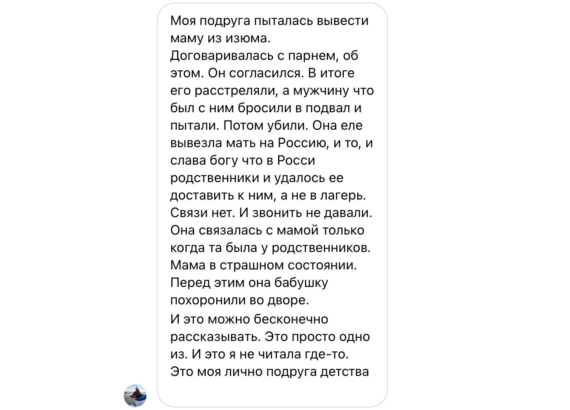

Today, I want to share two accounts about these filtration camps. The first one is from a text exchange between a Russian friend of mine (currently living in the US) and her Ukrainian friend (living in Kyiv). The translated text is below. The original messages (in Russian) are at the end of this post.

“I can tell you that I have a friend from Izium and another one from Mariupol. I know from first-hand accounts what ‘filtration camps’ are and what happens there. In Russia, they call them ‘green corridors’. But far from everyone makes it through them. Those who don’t pass filtration are shot. In the best-case scenario.

I’m writing this, and it seems like something like this can’t be happening. Such horrors in a modern world. Unthinkable. I never thought something like this would happen to us. Our grandmothers were right to say that there is nothing worse than war. I definitely understand that now.

In short, they don’t let you go to Ukraine. You can go to Russia, but not everyone makes it there. People are searched, undressed completely, they look for tattoos, etc. Then they ask about political positions, check your phone contacts, may beat you, may not beat you, may rape you, may not rape you, may simply, for example, take a mother (or any family member) to an unknown destination with no explanation. That’s the end. Either they got shot or they did whatever they want with them. No one will ever know. Those who pass are mostly taken to Siberia, to camps.

A friend of mine tried to get her mother out of Izium. She negotiated with a guy about it. He agreed to help. In the end, he was shot, and the man who was with him was thrown in the basement and tortured. Then they killed him. She barely got her mother to Russia. Thank God she had relatives in Russia and managed to get her to them, not to a camp. There was no communication. And calls weren’t allowed. She was able to get in touch with her mother only when she was at her relatives’ place. Mom is in a terrible condition. Before this, she had buried her grandmother in the yard. I could go on and on. This is just one of the stories. And I didn’t read it somewhere. This is my own childhood friend.”

The second story I want to share is a video testimony of a girl who escaped from Mariupol with her family. What follows is the translated transcript of the video; the original video is at the end.

“A filtration camp is not a settlement. It was just a convoy of cars. There were hundreds of cars in front of us and behind us. We were not allowed to leave the car. We were constantly being watched; they were observing what we were doing. Everything that a person does in everyday life, we had to do in the car. And that was very difficult. My legs were swelled terribly. My whole body hurt. We stood for two whole days and nights in that car, as did the rest of the people.

They said filtration starts at age 14. My sister is 12 years old. She stayed in the car. My mom couldn’t walk yet then, and they just decided not to bother with her. It’s a good thing she didn’t make it to that filtration. She might not have been able to take it, get scared by the things we heard. When my father and I were going to the filtration, I was reflecting and realized that it would be very hard for me. How could I renounce Ukraine?

I will never forget a conversation between two soldiers:

– What did you do with the ones who didn’t pass filtration?

– Shot 10 and then stopped counting. Wasn’t interesting.

They left me in the first room, in that filtration booth. They took my documents, scanned them. They fingerprinted me and in parallel checked my phone. There were five people in the room, five soldiers with guns. I was alone, and I was very scared. My legs were wobbling when the soldier that was lying on the mattress said, ‘If you don’t like her, there will be more women up ahead, we’ll find someone.’ They came to the conclusion that they didn’t like me and decided to let me go. What do I mean by letting me go? They just pushed me out. They didn’t let me wait for my father. They said, ‘If you have passed, you have to move on.’ We waited for 40 minutes for my dad. When we left, they told us to go to Berdyansk.

When we got to Berdyansk, my dad told us how he went through filtration. The most unpleasant questions were asked. Not only about the government and Ukraine, but about the whole situation – who he was, what he was doing here, what he was planning to do next. They even asked him, “Why don’t we cut your ear off?” We don’t know why we asked such questions. When they realized that his phone was empty, that there wasn’t even a SIM card and nothing to check there, they started pressing my dad and asking who he was. They wanted to get something out of him. They didn’t like the answers my dad gave them. They started pushing him and them they hit him over the head with something heavy. He says he doesn’t remember what happened next. He came to only when he was outside.

While we were driving from Berdyansk to Zaporizhia, we passed 27 checkpoints. It was the same thing at each checkpoint. But we weren’t asked about filtration here. Apparently, filtration was important in that place. When we saw a flag, the yellow and blue flag, we could not believe our eyes. Dad said that we’re celebrating too early. It could be another provocation, and we should keep quiet. We still had to be patient, just a little bit more. When we pulled up, we were told, “Your documents please.” Dad did everything in silence, was showing the car in silence. Because we were afraid that it might be another filtration camp, where people simply get caught in the first few seconds. When they saw the registration in our passport, they started asking, ‘Mariupol residents? What’s going on there? What horror have you lived through?’

Then we realized that these were our people, that we are already on our land. Because the occupants could not speak such beautiful Ukrainian. We saw their chevrons, their uniforms. And we realized that we were on our land. Even the sky was different there, it was clear. There was none of that dust that rises in the air from explosions. There was hope that we could get on with our lives. We could go on living. We deserved it after all the horror we’d been through. We really wanted to live.”

Original text messages to my Russian friend

Comments are closed.